South American Aviators and the Search for New Air Routes

By Dr. Pier Paolo Alfei (CLAS Visiting Scholar)

Between the end of World War I and the 1920s, several nations organized raids and international flights across countries and continents. These missions were driven by a mix of political, diplomatic, military and commercial goals. It was the golden age of aeronautical records and round-the-world flights. One of the most famous was the American one, which took place in 1924 with four Douglas World Cruisers (DWC): Seattle(Frederick L. Martin and Alva L. Harvey), Chicago (Lowell H. Smith and Leslie P. Arnold), Boston (Leigh Wade and Henry H. Ogden) and New Orleans (Erik H. Nelson and John Harding Junior). In the same period, many other countries, including Great Britain, Italy, France, Japan, the Soviet Union, Belgium, Portugal and Spain, organized international flights extensively studied by historiography.

Often overlooked were the flights that saw South American aviators take center stage during those years. For example, there were several unsuccessful and successful attempts to fly across the Andes Mountains with the aim of establishing air routes between Argentina and Chile. Argentine (Jorge Neubery, Alberto Roque Mascias, Pedro Zanni, Benjamin Matienzo) and Chilean (Clodomiro Figueroa) pilots attempted this feat. In April 1918, Argentine pilot Luis Candelaria was successful in flying over the Andes (on the Neuquén-Cunco route), followed a few months later by two Chileans: Dagoberto Godoy (Santiago-Mendoza) and Armando Cortínez Mujica (Santiago-Tupungato).

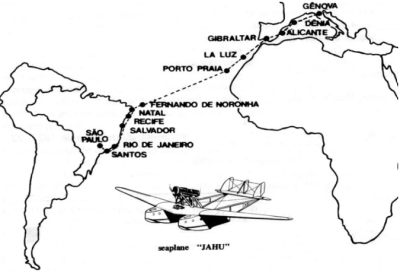

In the following years, other Latin American aviators attempted the even more arduous crossing of the Atlantic Ocean to establish a direct air route between Europe and South America. On 17 October 1926, João Ribeiro de Barros (together with João Negrão, Newton Braga and Vasco Cinquini) departed from Genoa with the seaplane ‘Jahú’. After a forced stopover of several months in Cape Verde due to damage to the aircraft, the Brazilians arrived in Santo Amaro, São Paulo. In the following years, the Uruguayan officer Tydeo Larre Borges attempted the same feat. His first attempt, departing from Marina di Pisa (Italy) together with his brother Glauco, Jose Ibarra and Jose Figolu, failed. In 1929, however, Larre Borges, with the Frenchman captain León Challe, successfully completed the flight from Seville to Natal (Brazil).

However, the most famous feat by a South American aviator in those years was undoubtedly the world flight under the Argentine flag attempted in 1924 by Pedro Zanni in a Fokker C-IV christened ‘Ciudad de Buenos Aires’. Departing from Amsterdam on July 26, Pedro Zanni and his mechanic Felipe Beltrame first reached Hanoi (Vietnam) and then Kasumigaura (Japan), following a route that mirrored Wilfred MacLaren’s world flight (1922) in the first part and Georges Pelletier D’Oisy’s Paris-Tokyo raid (1924) in the second one. Although Zanni did not complete the planned circumnavigation of the globe, his flight from Holland to Japan – around 6835 miles covered in 130 hours – was a huge media success in Argentina and around the world. The success not only brought national prestige but also acquired strong diplomatic significance. As can be inferred from contemporary chronicles, the festive welcome of thousands of Japanese ‘carrying Japanese and Argentine flags’ in Kagoshima and Tokyo in October 1924 was further proof of the excellent diplomatic relations between Argentina and Japan, which had already been consolidated since the (re)sale of two ‘Ansaldo’ battleships to the Land of the Rising Sun at the time of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905): as the Tokyo Asahi recalled at the time of Zanni’s arrival in Kagoshima, the two battleships had ‘contributed materially in bringing about victory’. The same emphasis on the ‘great assistance’ provided to Japan during the Russo-Japanese War was celebrated on several occasions during the receptions in honor of Zanni, and in particular in a speech by Baron Sakatani, President of the Imperial Aeronautic Association.

The achievements of Argentine (Luis Candelaria and Pedro Zanni), Chilean (Dagoberto Godoy and Armando Cortínez Mujica), Brazilian (João Ribeiro de Barros), and Uruguayan (Tydeo Larre Borges) aviators certainly constitute only a part, clearly not exhaustive, of the records and victories achieved by South American aviators in those years and more generally throughout the 20th century. Broadening the scope of analysis in terms of chronology and gender, one can mention the achievements of Peruvian aviator Jorge Chávez Dartnell and several female aviators often unknown outside South America, such as, Bolivian Amalia Villa de la Tapia and Brazilians Thereza de Marzo, Anésia Pinheiro Machado, and Ada Rogato, who have been feature in commemorative stamps in the early 2000s.

Equally worthy of analysis is the history of some unrealized South American flight projects. It was with great surprise, for example, that in the archives in Oslo I (re)discovered some documents relating to an Argentine Norwegian flight project whose destination was... the North Pole! The architect of the idea was Pedro Cristophersen, one of the most important figures in Norwegian emigration to Argentina. According to the project presented in 1924 to the Comisión Nacional Pro Vuelta al Mundo, the flight would have been carried out by Zanni together with the famous Norwegian polar explorer Roald Amundsen (a friend of Cristophersen). The polar flight could have been a great diplomatic success, as in the case of the slightly earlier Amsterdam-Tokyo raid. In Cristophersen’s words, ‘el viaje al Polo Norte bajo las banderas unidas de Noruega y la Argentina’ could have brought the two countries closer. A century later, many unknown stories related to South American aviators are still waiting to be rediscovered, and explored on an interdisciplinary level.