From Castro to Putin: Evaluating the Effectiveness of the West's Sanctions on Russia through the lens of the Cuban Embargo

By: Blake Marbaugh, CLAS Student Intern, Summer 2022

On February 24th, 2022, Russian troops invaded Ukraine to "demilitarize and denazify" the country from its defensive military and Jewish President. After three months of heavy fighting, the Russians have failed to achieve their primary goals, seeming to settle for occupying Kherson oblast and capturing the Donbas. In those three months since the invasion, the United States and its allies have punished Russia with heavy economic sanctions, causing the Russian economy to collapse almost overnight. However, Russia is still standing, inflation is down, the ruble is beginning to recover, and the Russian military can still conduct offensive operations in Ukraine. Why is this the case? Well, the answer may lie in what International Relations scholar William m. LeoGrande coined "the oldest and most comprehensive U.S. economic sanctions regime against any country in the world," the Cuban Embargo.

Before we begin, it would be helpful to examine which components are crucial to an effective sanctions regime to gauge the effectiveness of the Cuban Embargo and of the Russian sanctions. In Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, an empirical study of the effectiveness of economic sanctions throughout history, four main factors are identified that can gauge the effectiveness of this form of economic warfare. The first factor is how multilateral the sanctions are. It is crucial to deprive a nation of most if not all its trade with other nations to cripple its economy. The second is how comprehensive the sanctions regime is, as any gaps in policy may provide the target nation with a much-needed economic lifeline. The third is the economic stability of the targeted nation, as more unstable nations are more susceptible to shocks created by foreign nations' economic policies. Finally, the goal of the sanctions must be modest and limited as unrealistic goals lead to indefinite sanctions, which the target country will eventually adapt to.

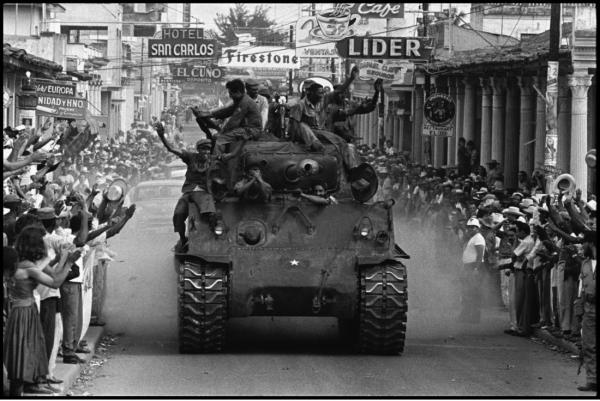

The U.S. embargo on Cuba began in October 1960 after Fidel Castro's communist government nationalized all U.S. oil refineries in his country without compensation. Castro's actions came in response to those refineries' refusal to process crude oil from the Soviet Union that the Cubans were beginning to import. In response to nationalization, President Dwight D. Eisenhower used the executive authority granted under the Trading with Enemies Act to ban all trade with Cuba except food and medicine exports. As internal U.S. government memos reveal, the purpose of the Embargo was to cripple the Cuban economy in tandem with covert CIA operations in hopes that the Castro government would collapse under the pressure.

President Kennedy would oversee the most "exciting" moments in U.S.-Cuban relations, ordering the Bay of Pigs invasion and averting thermonuclear war in the Cuban Missile Crisis. As Cuban exiles were being rounded up after their failed U.S.-sponsored invasion, Castro began moving to secure closer ties to the Soviet Union in hopes of fending off another invasion. In response, Congress passed the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, which barred any country from providing financial aid to Cuba and cut off all U.S. aid to those who wished to comply. After the Cuban Missile Crisis ended, the Kennedy administration instituted the Cuban Assets Control Regulations, banning travel between the two countries and freeing all Cuban assets in the U.S.

The Johnson presidency saw further expansion of the Embargo as it became clearer that previous policies would not bring about the desired collapse of the Cuban economy. What had become evident was that the Cuban economy was being propped up by the massive amount of aid and economic support that it received from the Communist bloc and trade with its Latin American neighbors. Johnson sought to make the Embargo more multilateral by having the Organization of American States (OAS) sanction the Cuban government. Castro responded to these actions by arming and supporting left-winged militant organizations throughout the Western Hemisphere. These events represented a shift in the goals of the Embargo; now, economic sanctions would remain on Cuba as punishment for destabilizing Latin America rather than a tool to force a regime change.

Until the end of the Cold War, every administration (spare Reagan's) would attempt some form of rapprochement with the Cuban government. Certain restrictions, such as those on travel, would be lifted or not enforced as secret negotiations with the Castro government were conducted. However, these incentives would not stop the Cubans from intervening in the Angolan and Ethiopia Civil Wars in the early 1970s, dooming any prospect of détente. During this period, the OAS also dropped its sanctions on Cuba.

The next stage of the Embargo came about after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Cuban economy suffered a 35% drop in GDP after losing its largest trading partner overnight. President George H.W. Bush and Congress smelt the blood in the water and quickly pushed through the Cuban Democracy Act (CDA). This law reimposed past restrictions on Cuba that had lapsed in the interim such as a ban on U.S. business subsidiaries from conducting business in Cuba. The law also stipulated that U.S. aid would flow into the country once the President had certified that Cuba had become a liberal democracy. The President would also "encourage countries that conduct trade with Cuba to restrict their trade and credit relations with Cuba."

The most comprehensive sanctions regime of the Embargo would come in 1996 with the passage of the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, a.k.a. the Helms-Burton Act. The scope of the Embargo was further expanded to include foreign companies trading with Cuba, threatening financial punishment to non-compliant businesses. Cuban Americans were also allowed to sue firms operating on land seized from them during the revolution. Most importantly, the law called on all U.S. representatives in international financial institutions to bar Cuban entry to their posted organizations. Cuba was effectively banned from the IMF, the Inter-American Development Bank, and other major western financial institution. Prior to this law, most of the sanctions placed on Cuba were placed under the discretion of the President. The Act codified the Embargo into law.

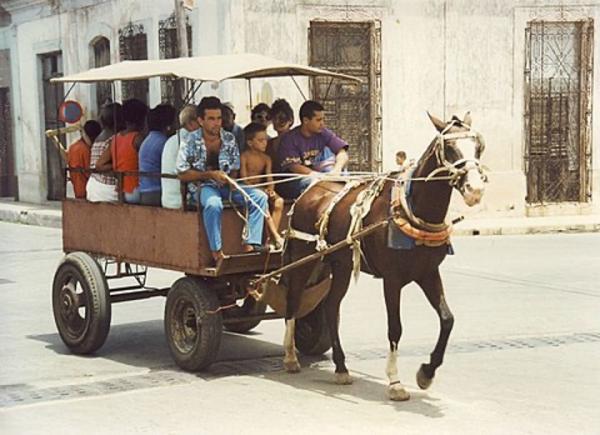

However, despite the broad scope of these two laws, Cuba remains standing. U.S. allies, chiefly Europe, do not enforce the Embargo. U.S. rivals are actively propping up the Cuban economy as the Soviets did half a century ago. The European Union is Cuba's largest trading partner and a primary source of tourists, one of the fastest-growing sectors of the Cuban economy. Venezuela and China have also made significant investments in the Cuban economy, spurring further economic growth. Domestically, the Embargo was and still is unpopular, which led to the rollback of some of the CDA and Helms-Burton Act provisions. The U.S. agribusiness lobby successfully had export restrictions on food to be lifted entirely, making the U.S. Cuba's largest supplier of humanitarian goods. Cuban ex-pats can still send remittances to their families back in Cuba, providing their economy with much-needed hard currency.

Now we return to the present day with the West placing heavy sanctions on Russia in response to its invasion of Ukraine. Let us start with a brief overview of the sanctions placed on Russia since February 2022. Initial sanctions were placed on Russian financial institutions, state bank assets in compliant nations were frozen, Russia's sovereign wealth fund was blocked, and Russia was removed from SWIFT. These policies have effectively isolated Russia from the West's financial system, devaluing their currency and obliterating their economic growth. Without access to SWIFT, it has also become more difficult for Russians to import consumer goods. The West followed up with restrictions on semiconductors to curtail Russian arms manufacturing to help deplete weapons stockpiles. However, restrictions on Russian oil and natural gas imports are absent in Europe. So far, it appears that the goal of these sanctions is to punish Russia for its invasion of Ukraine and extract such a high economic cost on Russia that Putin's war becomes untenable.

For this sanctions regime to be effective, The U.S. needs to look to its past pitfalls and the failure of the Cuban Embargo to avoid a similar result with Russia.

The U.S. has done well to ensure that its sanctions regime is multilateral. Half of the world's economic output complies with the financial restrictions imposed on Russia. Nevertheless, the West needs to worry about the other half of the world economy, especially India and China, its two most populous nations. India has helped Russia break records in oil revenue, while China is currently backing the ruble by using the renminbi and continuing to buy Russian commodities. These economic lifelines Russia is receiving are similar to the same lifelines that its predecessor extended to Cuba. Before Eisenhower started the Embargo, the Soviets had signed multiple trade deals with Cuba, giving them crude oil at a reduced cost while buying Cuba's chief export, sugar, at a markup.

Russian sanctions are not comprehensive, a significant issue that still plagues the Cuban Embargo. Many European countries party to the sanctions regime still import large quantities of Russian crude oil and natural gas. Europe is still contributing to the Russian war chest by buying Russian energy exports, undermining the stated purpose of these sanctions of halting the Russian War machine. Cuban remittances have also had a similar effect of undermining the effectiveness of U.S. sanctions on Cuba. By supplying Cuba with a means to gather hard currency, the U.S. has also allowed Cuba to buy goods on the international market.

Another issue was the economic stability of both nations before sanctions were enacted. Though the Russian economy was not at its best before it invaded Ukraine, state-owned financial institutions could still extract enough wealth from oil revenue to build a sizable sovereign wealth fund. This sovereign wealth fund has been critical to absorbing the economic shocks of the sanctions. Russia's crude is too valuable for the world to give up on and provides Putin's government with a steady revenue stream. Cuba's historical dependence on trade with the U.S. would ironically become its saving grace when the Embargo began. The pre-revolution Cuban economy was focused on exporting sugar to the United States. After the Embargo was put in place, the Cubans could quickly find a new market in the communist bloc.

Though the initial goal of stopping Russia's invasion of Ukraine is modest and limited, policymakers need to be cautious about shifting their goals, especially as the war drags on. A chief concern would be keeping the sanctions in place after the end of the conflict, which will lead to fierce debates in the White House and halls of Congress. No matter the outcome, policymakers should consider what happened when we set our sights on the ambitious goal of regime change in Cuba. As we can see, after 62 years of Embargo, Castro's government still rules Cuba even after his death. The Embargo has done nothing but strengthen the Castro regime and alienate the Cubans, making the prospects of a Cuban government friendly to U.S. interests in the future remote. The West needs to be cautious if it does not wish to create the same generational enmity in Russia.

Some policy recommendations may help improve the effectiveness of the sanctions placed on Russia, many of which would have improved the Cuban Embargo decades ago.

In order to make the Russian sanctions more multilateral to isolate the Russian economy, the West needs to work on its diplomatic efforts in the Indo-Pacific to deprive Putin of two of his largest export markets. It seems apparent that this strategy requires a deft touch, as the U.S. does not want to compromise its position in its ongoing "strategic competition" with China.

This reluctance to rock the boat in the Indo-Pacific is apparent in the lack of pressure the Biden administration has put on India in response to its dealings with Russia. The close relationship between Russia and India dates back to security ties formed between the two nations during the Cold War. Thanks to these ties, India's military arsenal depends on Russian technology and spare parts only manufactured in Russia. This is an aspect of the Indo-Russian relationship that the West has the means to change. Europe, the U.S., and other allies need to increase arms sales and technology transfers to India in hopes of weaning them off their reliance on Russia, hopefully trading these arms for at least some form of sanctions compliance.

A more complicated matter is getting China to comply with the West's sanctions regime. There are a few suggestions to get the ball rolling. First, the U.S. and its Pacific allies need to relax their tendencies to antagonize the Chinese publicly. Increased Freedom of Seas Operations in the Taiwan strait and recent comments made by President Biden are unnecessary and counterproductive in a situation where their cooperation is needed. Second, the West should focus on finding common ground with the Chinese to help them understand why punishing Russia for its invasion is in their best interest. One area of common interest is the disastrous effect the war has had on the global economy, especially during a sensitive time for China as it continues to battle COVID-19 outbreaks. The upcoming 20th party congress will see Xi Jinping announce his intention to remain in power for a third term citing continued economic growth. It may become more appetizing to punish international pariahs whose wars slow economic growth, such as Russia. In an increasingly globalized society, war is bad for business. China has shown a willingness to at least acquiesce to some Western demands, such as refusing to send military equipment to Russia.

Europe needs to cut its dependence on Russian oil and natural gas to make the sanctions comprehensive. This policy prescription is easier said than done. It will take time for Europe to find new fuel sources and invest in renewable energy. However, if Europe pulls it off, the E.U. will enjoy an unprecedented amount of geostrategic independence down the road.

Finally, Western policymakers need to be cautious of mission creep. It may shift their current modest goals to something more ambitious and unattainable. The U.S. and its allies need to maintain that the goal of these sanctions is to end the war in Ukraine. They must also discuss what sanctions would be kept after the war's conclusion. The West also needs to communicate to the Russians the conditions in which the sanctions will be lifted and, most importantly, follow through on cutting these sanctions when the conditions are met. Otherwise, we might get caught in the same endless Embargo the U.S. placed on Cuba.

For further reading, I would highly recommend William M. LeoGrande's article, "A Policy Long Past Its Expiration Date: U.S. Economic Sanctions Against Cuba," for a brief history of the Cuban Embargo and an analysis of its overall effectiveness.

CONNECTING TO THE K12 CLASSROOM

- What is the Cuban Embargo and what is its significance for Cuba and the US, both economically and culturally?

- In what ways has the Cuban Embargo impacted immigration?

- List three ways in which present-day Russia can be examined through the lens of the Cuban embargo.

- Why is the Cuban Embargo still in place? How might this impact Cuban voters and general relations?

- At all levels, World Language students can research this topic and Presentational (writing and/or speaking) and/or Interpersonal Communication can be assessed. These all could also be discussed in AP Government and/or History.