A Tale of Two Colonies: Examining the Filipino and Colombian elections and their victors

By: Blake Marbaugh, CLAS Student Intern, Summer 2022

(Right) Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. Contributed Photo.

On June 19th, 2022, Colombia elected its first left-wing president, Gustavo Petro, and first African American vice president, Francia Márquez, after a tight run-off election. This unprecedented event appears to be the start of a sea-change for the nation, as Petro seeks to re-evaluate most, if not all, the policies instituted by his predecessors, especially his country's war on drugs and its relationship with the United States. Ferdinand “BongBong” Marcos was sworn in as president of the Republic of the Philippines on the 30th of June after scoring a landslide victory with the support of outgoing President Roberto Duterte. Bongbong's success continues a trend of democratic erosion, with many Filipinos and international relations scholars fearing that Bongbong's family ties may lead him to reinstate a dictatorship similar to what his father established in 1972. These two former Spanish colonies appear to be heading in opposite directions. As Colombia embarks on a journey toward a new, uncertain future, the Philippines seems to be creeping towards its authoritarian past. I want to examine this divergence of paths, first by looking at the contemporary political history of Colombia and the Philippines, then focusing on why Petro and Bongbong won their respective elections in hopes of finding an explanation for why these countries seem to be on opposite trajectories.

Contemporary Colombian politics began with the end of the National Front, a power-sharing agreement between the country’s dominant Conservative and Liberal parties. The National front formed to decrease polarization within the two-party system, which had led to violence in the 1950s and 60s, with the central premise being that both parties would always have some form of power in government. The agreement quelled violence within mainstream politics while pushing more fringe ideologies out of the system, especially leftist groups. These Left-winged dissidents who could no longer participate in Colombian politics began to organize into militant groups to combat the National Front through guerilla warfare. The most infamous groups were the April 19th movement (M-19), the National Liberation Army (ELN), and theRevolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

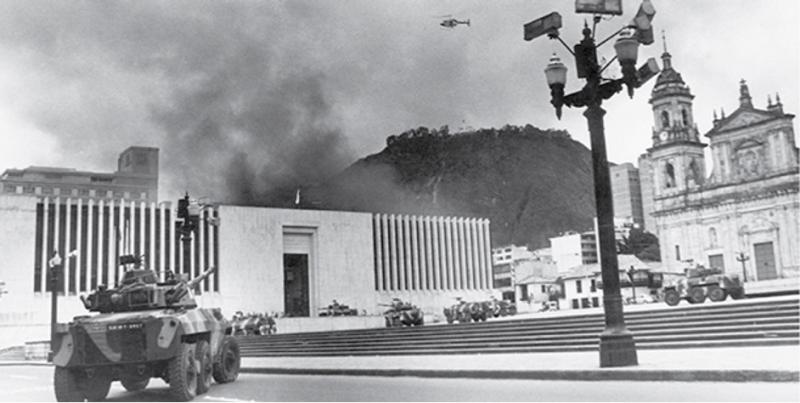

The rise of these guerilla groups, compounded with the birth of drug trafficking and the security issues brought about by these two factors, would be the central struggle of the Colombian government in the post-National Front Era. In urban areas, M-19 members carried out high-profile attacks that degraded citizens' confidence in their government. In the countryside, FARC and the ELN waged a guerilla war against the Colombian army. While Narco-terrorists (the most famous and active of which was Pablo Escobar) ordered and carried out targeted assassinations against government officials that supported the extradition of drug traffickers to the U.S. Security forces were spread too thin dealing with these issues, leading to the rise of vigilantism and right-winged paramilitary groups.

This security situation severely affected the Colombian economy, society, and foreign relations. The economy slowed due to a lack of foreign investment, leading to high unemployment and creating a recruiting pool for cartels, paramilitaries, and guerrillas. As confidence in government shrank, society became more polarized as Colombia became dependent on U.S. security and economic assistance.

The security situation began to improve thanks to negotiations with some leftist groups. In 1990, M-19 agreed to lay down its arms to participate in drafting Colombia's 1991 Constitution. Over 20 years later, in 2016, FARC finally agreed to a peace agreement that allowed the group to participate in government. A peace and reconciliation committee was also established to distribute reparations to victims of the conflict and carry out justice on those who violated human rights during the conflict. In 1993 Pablo Escobar was killed by the Colombian government, bringing an end to high-level narcoterrorism in the country. However, the ELN has continued its guerilla war, apparently taking on FARC members who were dissatisfied with their group's peace agreement.

These events bring us to this year's historic presidential election; at the forefront of people's minds was the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. The economic devastation and resulting high unemployment brought about by the pandemic, paired with the lackluster government response, left a majority of Colombians dissatisfied with the government and the current capitalist economic system. When the Colombian people began to protest about their living conditions and the country's general financial state, the government responded with riot police. The resulting confrontations between angry protestors and trigger-happy riot police left dozens of protestors dead and hundreds injured, sparking more anti-government protests.

These events doomed the Conservative government in power, making them wildly unpopular as Colombia sought a new path for their country outside the moderate left-right divide that had typified their country's politics for about two centuries. This break with tradition catapulted Gustavo Petro to victory in the first round of the 2022 presidential election and is why Rodolfo Hernandez, who was not a Conservative party member, was his opponent in the second round.

Petro, a former M-19 guerilla, centered his campaign promises around taxing the rich to help pay for an expansion of Colombia's social safety net, updating and expanding infrastructure to encourage green industry while cutting his country's production of fossil fuels, and re-evaluating his country's war on drugs. This re-evaluation will be paired with a renegotiation of free trade agreements with the U.S. as he hopes to reconfigure his country's relationship with its historical ally.

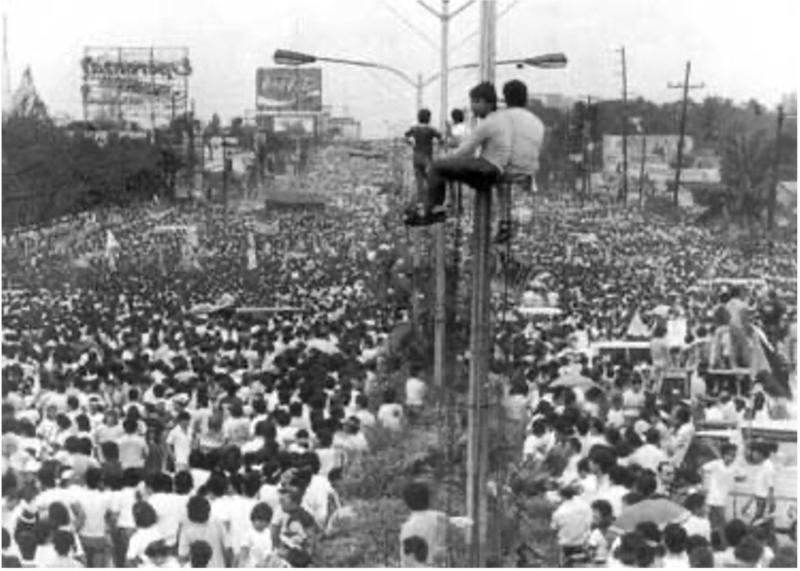

The government of the Philippines has had to contend with a similarly negative security situation to that of Colombia as it tries to find stability in a post-dictatorship democracy. Modern Philippine politics began with the People Power Revolution that overthrew dictator Ricardo Marcos in 1986. The revolution was triggered by the assassination of one of Marcos's opponents in the leadup to the 1985 election and him calling an unconstitutional snap election immediately after. The revolution was popular, including the Philippine military, which would depose Marcos in a coup, setting a precedent for military intervention in political matters.

The new democratic transition government tasked with writing a new constitution had to fight off three coup attempts before it could draft the constitution in 1987 that reinstated civilian, democratic rule. The Constitution stripped the presidency of many of its powers. It implemented a checks and balances system in hopes of preventing a government takeover similar to what Marcos did in 1972. The country also adopted a multi-party system and attempted to strengthen its institutions to improve long-term stability. However, despite its name, the People Power Revolution was more a return to form than a genuine change in the balance of power in Philippine politics. The old political dynasties that had ruled the islands since the Spanish colonized them returned to power, leading to pork-barrel politics and corruption.

These two issues have become endemic in Philippine politics, as every administration since the revolution has been mired in some form of scandal. The Fidel Ramos administration, the first since the new constitution was enacted, remained relatively scandal-free but reinstated the death penalty. Joseph Estrada, Ramos's successor, was embroiled in a scandal that ended when the military deposed him for attempting to prevent his impeachment trial from going forward. Estrada's vice president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, assumed power, running for and winning the presidency in 2004 after rigging the vote and fighting off a coup attempt. Arroyo's unpopular presidency was followed by the relative calm and stability of the Benigno Aquino presidency. This calmness came to an end with the election of Roberto Duterte. He oversaw a massive war on drugs that left tens of thousands of Filipinos dead, a politicization of traditionally apolitical government institutions, and a break in relations with the nation's chief ally, the United States. Meanwhile, the country has been fighting Muslim separatists such as the Moro Liberation Army and the Communist New People’s Army left over from the Marcos dictatorship.

This year's elections were more about what was not on the mind of the average Filipino voter than what was their concern. This ignorance is partly due to Philippine politicians rarely worrying about popular sentiment, as most power in their system comes from dynasties and political allies. This focus on dynasties and alliances appears to have manifested in the 2022 elections through its victors, Bongbong Marcos, son of former dictator Ricardo Marcos and his vice president Sara Duterte, daughter of the outgoing president Roberto.

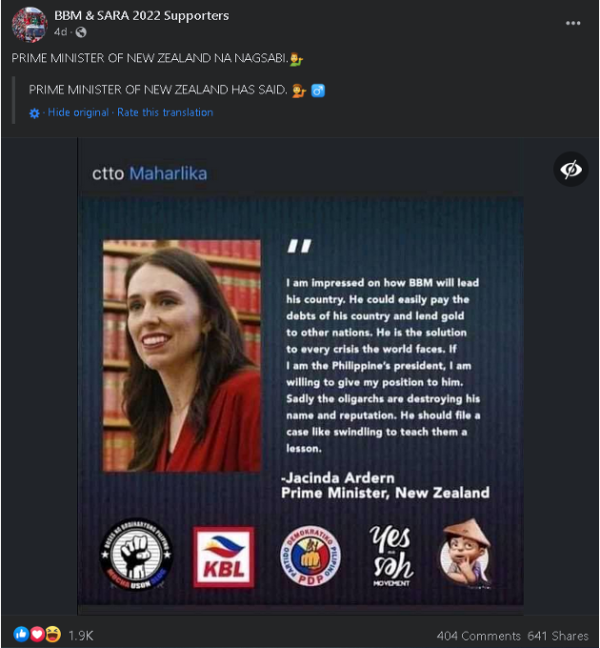

Bongbong did not attend a single televised event and never stated a concrete policy position throughout his campaign, making only vague promises to heal the divides within Filipino society. What is interesting to note is how Bongbong handled his family's controversial past. In interviews, Bongbong frequently downplayed his attachment to his father's dictatorship. However, on social media, his supporters and social media managers ran an effective disinformation campaign that lionized his father's dictatorship, rebranding it as the modern Philippine's Golden Age, despite the rampant human rights abuses and economic stagnation under it. The effectiveness of this disinformation campaign lends itself to the young age of the average Filipino voter, 25.7 years old. Most of them were born after the end of the Marcos dictatorship. The pandemic may have also led to a growth in populism as many looked for strongmen to guide them through the harsh economic situation.

Since Bongbong ran with the same party as Duterte, it is believed that he will follow through on Duterte's policies. Such policies include further investments in infrastructure and continued strategic realignment toward China. An explanation for why such a realignment may be occurring is the fear that the Philippines' armed forces will never be a match for the Chinese military. The rationale seems to be money spent on the military would be better-used building infrastructure and paying for social programs. Such a realignment may create tension between Bongbong and the military, as his country's armed forces depend on U.S. security assistance to fight the insurgencies occurring throughout the country.

With the current situations established, we can try to ascertain why both nations are on such different paths. First is the security issue. Though both countries face similar security issues, namely communist guerilla movements, the outcomes of these conflicts have been markedly different. An explanation of why this is the case may lie within the different actions the Colombian and Philippine governments took when combating their insurgencies.

The Colombian government was able to pump a significant amount of money into its armed forces to fight FARC in the early 2000s. These funds led to an offensive that contributed to FARC eventually coming to the negotiating table.

The Philippines, on the other hand, have left their military with very little money, with their budget hovering around 1% of the country's GDP since the People Power Revolution. This policy may stem from fear within the political establishment of another coup. Nonetheless, these cuts in funding have led to a drop in the effectiveness of the Philippine armed forces in combating leftist guerillas and Islamic insurgents. The inability of the underfunded Philippine army to force the guerillas to the negotiating table may be why these conflicts appear to have no end in sight.

Both countries also seem to be diverging regarding their futures as democracies. Colombia is a strong democracy and looks to remain one for the foreseeable future. Though Petro represents a split away from traditional establishment politics, it is not a departure but a continuance of Colombia's strong democratic traditions. Since its creation in 1830, Colombia has been a democratic republic with few interruptions. Almost 200 years of democracy makes it extremely difficult to change this status quo, and authoritarian actions are incredibly unpopular. The Conservatives found this out when they violently cracked down on protests before this year's election.

In June, the Filipino people voted to continue the democratic backsliding the country was already beginning to experience under Duterte. The instability of the democratic government has been blamed for the economic and security issues that plague the country. Fears of a coup, political dynasties, and pork-barrel politics have weakened the government's ability to function effectively and resulted in a loss of confidence in the Filipino people.

What exacerbates this issue is the lack of a robust Democratic tradition in the Philippines. The Philippines is a relatively young country, only coming into existence as an independent state in 1946. From when Marcos seized power in 1972, the president enjoyed sweeping powers with little to no checks and balances. In reality, the Philippines has only existed as a Liberal Democracy since 1986, putting it in the same situation as many post-Soviet Eastern European countries that have had severe issues with instability and rising authoritarianism and populism, such as Poland and Hungary. However, unlike these fledgling democracies, the Philippines possess an elite class that dates back to before Spanish colonization and holds significant power. This class has degraded Philippine democracy since its inception and has grown complacent with the trend of illiberal Democracy that the country seems to be falling into.

Though they are on diverging paths, both countries share one similar foreign policy prescription, distance from the United States.

Petro’s proposed policies for tacking the war on drugs would, in effect, cut his reliance on U.S. security assistance. Legalizing the cocoa plant, one of his policy positions, would eliminate one of the country's main contributions to halting the drug trade and create a rift between the U.S. and Colombia. Another point of contention is Petro's willingness to engage with Venezuela, a U.S. rival, in hopes of reopening trade and quelling violence in the border regions.

Bongbong may continue his country's shift due to the aforementioned security issues and economic concerns. The infrastructure investment offered by China's Belt and Road initiative aligns nicely with Bongbong's policy prescriptions. Increased economic investment and trade with Beijing could help the country's financial woes.

These factors leave the United States at a crossroads regarding whom it wishes to ally with, especially now as we continue our strategic competition with China. Do we fall back on old Cold War habits and support authoritarian regimes that are at odds with our liberal form of government as long as they stand against our rivals? Or do we chart a new course, aligning ourselves with ideologically disparate nations that still function as liberal states but are ideologically opposed to us?

For further reading, I’d highly recommend the Center For Strategic Studies’ analyses of both the Philippine and Colombian elections

CONNECTING TO THE K12 CLASSROOM

- In what ways are the election processes and party systems of the Philippines and Colombia similar to and different from those of the US? Have students look into all three countries to compare and contrast.

- In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals. How does the political climate impact these specifically?

- The Philippines and Colombia share a history with both Spain and the US, which should each be examined separately. What is this history and in what ways do we see this cultural connection? What is their current relationship and how might this impact their politics, such as their financial state?

- “Both countries share one similar foreign policy prescription, distance from the United States.” What are the possible implications for the US? How might this impact Venezuela-Colombia relations?

- Colombia has its first African American vice president, Francia Márquez. How might gender, class and cultural norms impact how she has been and will be perceived by the general public and other politicians?

- Petro’s election is in line with left-leaning states coming into power in Latin America. What is the cause of this trend and possible future implications?

- At all levels, World Language students can research this topic and Presentational (writing and/or speaking) and/or Interpersonal Communication can be assessed. These all could also be discussed in AP Government and/or History.